Sir David Attenborough is once again captivating viewers with Mammals, the latest production from the BBC Studios Natural History Unit. As the six part series continues its Sunday night broadcast, TVBEurope talks to Will Lawson and Stuart Armstrong, respective producer/directors of the Cold and Dark episodes, to find out more about the challenges they faced and the innovative technology they used to overcome them.

You used extremely sensitive cameras to capture the behaviour of the animals. Tell us more about that?

Will Lawson, producer/director Cold episode:

For the Cold episode, we aimed to predominantly film during daylight hours, however, filming during winter months at polar (high) latitudes meant day-length was often severely limited. As a result, using cameras that extended the usable light beyond sunrise and sunset was important. For most of our long lens filming (when higher frame rates were not required) we opted for the RED Gemini. It guaranteed us an extra stop (or two) of light (without losing quality or dynamic range), which often made all the difference waiting out on the tundra, sea ice or in dense boreal forests.

For one sequence, to help us increase our chances of gathering less predictable behaviours, we incorporated remote camera traps. We used Cognysis camera trap systems with Sony A7siii cameras for several reasons, including their low light capabilities. Using the A7siiis we were able to extend the filming window significantly and compensate for the extremes of weather and glare that can occur in snowy locations. We could set the cameras up to expose for high glare/sunny days by manually stopping them down and using ND filters, while remaining confident that the cameras’ impressive (auto) ISOs would still be able to produce quality results on darker, cloudy days.

Another sequence was filmed in the dark. The aim was to show hibernation, or rather a mammal coming out of hibernation. As the biological process itself involves the mammal warming up, we wanted to film in thermal infrared; to do this we decided to use a combination of thermal cameras – the FLIR 8500 and InfraTec’s IR10300.

Stuart Armstrong, producer/director, Dark episode:

We used a raft of different cameras to film at night, with each sequence often requiring a different approach. For low light filming where we were relying on moonlight alone we used Sony A7S3 and FX6 cameras. Both have the same extremely sensitive full-frame sensors, and were the most sensitive available to us during filming. We also increased this sensitivity on some of our A7S3 cameras by adapting them slightly. Filming under moonlight, when light is so minimal compared to daytime, every little helps.

For sequences where we knew the behaviour would only happen on moonless nights, or if the location didn’t lend itself to low light filming because of often cloudy skies or forest to contend with, we opted to use thermal technology to film. Thermal cameras have advanced a huge amount in the last decade and the latest systems are incredible, both in resolution and range.

For a couple of sequences filmed in interior situations (armadillo denning inside an abandoned building and fishing bats roosting in a sea cave) we opted to film in IR to avoid disturbance to the subjects. For armadillos, we used IR-adapted ZCams as part of a fixed rig, operated remotely over 1km away from site. For fishing bats we used an IR-adapted RED Gemini.

How many cameras did you use?

WL: When filming in standard long lens situations, one Red Gemini would often be in use. For camera trapping needs we used up to six of the A7siiis at any one time. For the thermal filming, we had up to two thermal cameras filming simultaneously.

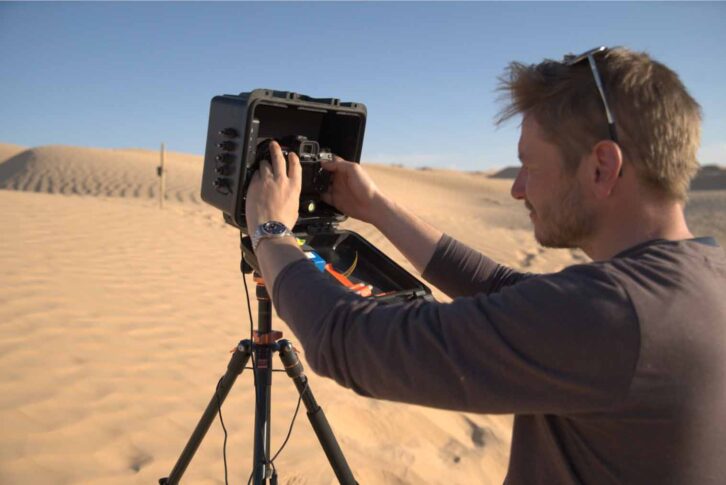

SA: For the fennec fox shoot, we had both manned and unmanned cameras. Two cameramen each worked with adapted A7S3s, but we also deployed half a dozen A7S3 camera traps mounted in the Cognysis trap system. For armadillos, we rigged four IR-adapted ZCams on hotheads, to cover all locations within the abandoned building the armadillos frequented.

How were they developed?

WL: The only ‘development’ we undertook was to 3D print an extension tube for one of the thermal camera lenses – which allowed us a slightly tighter shot and a narrower depth of field than the original lens allowed. This was not a permanent alteration however, but simply a temporary modification in the field.

SA: Modifications (e.g. IR conversions) were done by the camera team.

What advantages did the cameras used on these shoots give you over equipment you have used previously?

WL: Apart from what I already mentioned above, the Sony A7siii is very versatile for a pro-consumer camera, delivering broadcast-quality footage at a range of frame rates. Combined with its compact, lightweight size, it meant that when not in use in camera traps, it was a good back-up option for a range of other shots e.g. on a handheld gimbal, in an underwater housing, or for filming northern lights.

Our choice of thermal imaging cameras (and their associated lenses), allowed us to film our small subjects (± 5cm in length), warming up in greater detail; thermal imaging at a macro level felt a fresh perspective. The cameras also allowed us the ability to fine tune the thermal parameters after filming had taken place. This meant we could primarily concentrate on capturing the behaviour, safe in the knowledge that we could fine-tune the thermal settings (maximum and minimum temperature range) in post. The cameras could also film at very low frame rates, allowing us to show the process of warming in a more dynamic way.

SA: The A7S3/FX6 systems were so much more sensitive than previous low light technology that the BBC Studios NHU has used before to film under moonlight. We tested the cameras with a range of fast lenses in advance to find the “sweet spot” for ISO/gain where noise would be minimal, which, incredibly, was approaching 100,000db. Post production techniques have also advanced enormously, enabling us to clean up each image to reduce the inevitable noise, even where we had pushed the ISO to over 250,000. The cameras are so affordable too. It was a real game changer especially for filming fennec foxes.

Did using the specialist cameras present any unexpected challenges?

WL: The thermal cameras we used are designed primarily for industrial applications in controlled conditions, rather than for filming unpredictable wildlife – something we were aware of, and partly the reason we chose them – but this meant that portability could be an issue. As a result, changing camera position quickly was definitely a two-person job, which could be tricky if space was limited or your “extra pair of hands” was preoccupied. The thermal cameras also required 24-volt power, so we needed to source and hire high capacity (and portable) batteries in-country (being unable to fly with them), which was more of a challenge than we anticipated.

SA: The one issue we couldn’t overcome with low light filming was the limitation on lenses available. We really needed lenses with f2.8 aperture minimum to catch enough light for exposure. That limited us in range, with the longest workable lenses being Canon 400mm f2.8. For camera traps this was fine, as we could use wider, faster lenses, but it was limiting for long lens work.

Were there any particular aspects from previous shoots that you’ve worked on that made your life easier this time around?

WL: Having spent the last eight years working in cold environments, I’ve become accustomed to the fact that low temperatures and electronics simply do not play nicely together. This helped anticipate potential weak points and mitigate or plan redundancies for them. A few examples of the more unique considerations when filming in cold environments are: having strict protocols for re-warming equipment to avoid condensation issues or damage from thermal stress; making sure cables are ‘arctic grade’ to allow them to be re-coiled after use and prevent breaks; always having canned air at the ready – snow is worse than dust, clogging in its solid form and shorting electrics when it melts; not relying only on touch screens for camera control as they often slow down significantly in the cold; body heat is the most effective way to keep spare batteries warm. The list goes on…

SA: Not really, other than 20 years experience of film-making/working on complex and often remote shoots. Night filming is hard, both technically and physically, but the rewards were huge for this particular series. With most mammals being nocturnal, we had a raft of stories that hadn’t been told before, which was very exciting in an industry where new stories are the hardest to come by.

What type/s of lenses were used on your shoots?

WL: For our camera traps the Sony 24-70 f/4 and Sony 16-35 f/4 were our go-to lenses, as well as Canon 50mm f/1.4, Canon 85mm f/1.8. For our thermal cameras we used a combination of the following lenses (equivalent ‘mm’ on a 35mm sensor, listed for reference): 45 degree = ~50mm (on 35mm sensor), 25 degree = ~100mm, 15 degree = ~170mm, 6 degree = ~400mm. When filming on the Red Gemini our go-to long lens was the Canon CN20, 50-1000mm and often the Canon CN7, 17-120mm for wider angle versatility. In cold environments, changing lenses in the field is never ideal, so having dynamic zoom lenses for both behavioural and scenic filming is important.

SA: Our go-to long lens on low light shoots was Canon 400mm f2.8 mk3. It was the best, fastest, longest lens available. We did also try the “Sigmonster” – Sigma 300-800mm f5.6 but this was only fast enough to use on nights when the moon was full. The Saharan dunes where we filmed fennec foxes was the only place where this lens worked, as the sand was so light and reflective, giving us the increased levels of moonlight required. Having confidence in regular clear skies also helped.

With reference to the Cold episode, was any of the equipment developed specifically for the shoot?

WL: For one sequence we wanted to film underwater behaviour in a very cold river. The problem was, if we had a camera operator in the water the behaviour would be unlikely to happen, and if we left the cameras unattended there was a chance they might be “investigated” by passing wildlife. We also had no way of knowing the direction of behaviour. So, we needed multiple rugged, discreet cameras that could run for long periods in cold water, and that we could monitor and operate from the riverbank. With all this in mind, our BBC in-house innovation team developed a system of GoPro sized cameras that, through a single cable, could all be remotely powered, monitored, and operated by one person. The system allowed four independent cameras to be powered by one 98Wh v-lock battery for several hours and be monitored/operated through a cabled wifi transmitter/receiver system. The system worked and was completely ignored by any wildlife.

Can you expand on the range of different filming techniques you talked about?

WL: Dramatic improvements in battery technology for aerial drones and remote camera traps allowed us to spend longer in the air and leave compact camera systems unattended for weeks at a time, even in the coldest conditions. In the past the impact of the cold on battery life has been a huge limiting factor for both these filming techniques.

For example, while filming in Svalbard, the battery now used in the inconspicuous DJI Mavic 3 Pro drone, allowed us to fly in temperatures of -20C for over 30 minutes. This allowed us to capture dramatic views at a distance and follow unfolding behaviour for longer. Without this increased battery life, I think the chances of us successfully documenting a polar bear hunting reindeer in a long-distance pursuit (the ambition of the shoot), would have been extremely slim. We also devised new ways for our film teams to stay safe and (relatively) warm in the frigid elements for longer, without the time-consuming process of having to return to a base.

Again, in Svalbard, we worked with our fixer and expedition leader, Oskar Strom, to design and have made small, self-contained pods. Each unit was meticulously designed to provide two people with shelter and the necessities of energy, warmth and water 24/7 whilst being portable, each light enough to be pulled by a Ski-Doo. These pods were custom-made for the harsh Arctic conditions, and transformed our filming approach, allowing us to live self-sustained in extremely remote locations, while maintaining our ability to relocate and move with the wildlife for weeks at a time.

At any point, did the animals demonstrate awareness of the cameras’ presence and, if so, what was their reaction?

WL: We did have footage on our remote cameras of animals showing interest in them, but then moving on. On one occasion a grizzly bear (not the mammal we were hoping to film) did systematically “investigate” four of our camera traps, providing us with footage of each camera trap being pushed over, one after the other. Fortunately, there was no major damage, but the bear did completely scupper our chance of filming the intended mammal.

Were there any particular lessons learned during these shoots?

SA: One aspect I hadn’t envisaged was how the height of the moon dramatically changes the image. I was just focused on having enough light for exposure. Just like when filming in the day, it is preferable to film when the light source is low to bring contrast into the shot, and also back/side light the subject. A high moon brings a washed out, flat image. So moonrise and moonset were the sweet spots for filming.

But you only get one moon rise/set each night, so we had half the opportunity to film that you do during the day. Through rigging multiple camera traps out in key positions we did increase our chances of hitting the timing right, and doing this over an extended period gave us enough material to construct what is a very novel sequence of a rarely filmed – actually rarely seen – animal.

Were there any absolute stand-out moments for you and your team during the process?

WL: I would have to say the moment I received our camera trap cards back from Alaska. They were posted back to me nearly six weeks after we had left the remote cameras behind, in the hope they would capture a filming first – wolverine kits emerging from their snow den on the Alaskan tundra. We left the camera traps with no way of knowing if there were kits in the den, if the cameras would record, if the snow would melt and they would start to list or fall over completely, if the lenses would freeze up or if the batteries would last. There was plenty that could go wrong. After waiting on tenterhooks, I was the first person to see what the cameras had recorded… and after many shots of blowing snow and passing wildlife, there it was. Footage of a mother wolverine bringing its kit above the snow for the first time. Against the odds, the cameras had worked.

SA: Many! But one shoot stands out for me. Filming a leopard stalking and hunting sleeping baboons 20 metres above the ground in an ebony grove in Zambia. She only did this on the darkest of nights, when her night vision gave her an advantage over her diurnal prey. Even so, seeing her leap many metres between branches at such a height and in such darkness was awe-inspiring.

Finally, what’s next for you – do you plan to use the tech from these shoots on further projects?

WL: Filming in cold environments comes with a raft of unique challenges, as well as opportunities – working out how to mitigate the former while maximising the latter will, I’m sure, be an ongoing creative struggle. But I’ve thoroughly enjoyed sourcing, testing and developing the right tools to document in environments that are as beautiful as they are unforgiving (to kit and crew). I’ve no doubt I will find myself back in the snow and ice soon, putting a new piece of filming equipment to the test.

SA: I loved the challenge of making a show about nocturnal mammals, but I’m hoping for more daytime shoots in the near future.