The 23rd Rory Peck Awards saw two of the three categories won by women filmmakers, and shocking evidence of a strong, and well-organised undercurrent of fascism in American society.

The 103 entries, with credits going to freelancers from over 50 nations, included 29 entrants in the news category, 40 in the news feature section and 34 in the Sony Impact category. In total 98 freelancers entered stories, of which 20 per cent were women freelancers.

The threat of death or the smell of death was common to all nine finalists, as typified by the news category finalist Al-Emrun Garjon of Bangladesh with The Rohingya Crisis. For AP he tracked the Rohingya Muslims, as they fled the Rakhine province in Myanmar, between September 2017 and April 2018.

Appalled by the violence and multiple atrocities, he put his life at risk when Bangladesh had not yet decided officially to accept the huge exodus.

“They did not allow journalists to come to the refugees, so we had to create an alternative way, walking close to the Myanmar border fence,” says Garjon. “We had to walk miles and miles to get to the border, and if the Myanmar border security force had seen us they would have shot us. And the Bangladeshi border force detained us several times.”

The Google sponsored News category

Mikel Konate of Spain with Rescue Mission in The Mediterranean Sea won, and Humam Husari of Syria with Coverage of the Siege of Ghouta for ITV News was the second runner up.

Konate joined the crew of Mission 23 of the Open Arms project, his fourth such trip, for a “dramatic and very complicated rescue”.

The ship was in the central Mediterranean, in rough weather, which ruled out fresh mass sailings from Libya. “Suddenly we had a call saying there was a target 12 miles from our position, but almost 200 people in what was a giant dinghy had left the day before. They spent a whole day in the sun, then a whole night with nothing to eat or drink, and people started to die,” he adds. “It was a vey sad mission.”

Some people fell out of the boat, and when found the survivors were standing on 13 who had simply died in the crowd.

“People are dying and that is unacceptable. There are international laws and sea laws, but we cannot leave people to die there. What saddens me more was the condition of the women on that boat. They were covered in assault wounds, and some were almost naked through sexual abuse,” says Konate.

The News Features Category

Orlando De Guzman and Zach Caldwell, a Filipino/American combo, with Charlottesville Race and Terror, and Javier Manzano of Mexico with After ISIS were joint runners up to

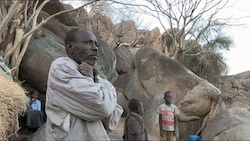

Roopa Gogineni of the USA with The Rebel Puppeteers of Sudan. This was shot in Sudan’s Nuba Mountains, with locals using a Spitting Image type satirical puppet show to poke fun at a government that throttles all journalism.

“The subjects in my film are puppet artists but they are also holding power to account in their own way. Their work, like the work of journalists, is important for building a healthy and open society,” says Gogineni. “A South African puppeteer made the puppets, and he came to the NUBA region to train the local people. They were very funny.”

The Sony sponsored Impact Current Affairs category

Deeyah Khan and Darin Prindle won this award with White Right: Meeting the Enemy. The other finalists were Mohammed Al-Mekhlafi with Conflict and Cholera: Yemen’s Catastrophe, and Alexander Houghton with Venezuela: Smuggling Dreams.

Khan had previously made a film about honour killing called Banaz: A Love Story, and one about terrorists called Jihad: A Story of The Others; so she already was a veteran of hate vibes. Getting behind the hatred and ideology of America’s national socialist movement, and talking to head of the neo-Nazis Jeff Schoep, was uncomfortable and difficult but had to be done, despite being pregnant at the time.

“Being a woman of colour and being confronted by people like that was really uncomfortable but also really life changing for me in many ways,” says Khan. ”I never thought I would be able to cultivate friendships with people I dislike and disagree with. I hate their views but somehow it was possible for us to forge some kind of human connections.”

Khan wanted to sit down human-to-human and see if it was possible to recognise and find humanity, and see if the white supremacist could see her humanity.

“The only way to do that was for me to leave all my emotional baggage at the door. There is the carrot: whatever platforms they can get they want because they can say what they want to, and it is also a recruitment tool,” she says. “They were expecting me to get offended and get pissy with them. Their movement is hyper masculine, based on aggression and dominance, but you do not have time to be scared.”

Khan and Prindle found a fascist militia of 75 men along a deepest Virginia dirt road, and made the mistake of not telling anyone where they had gone.

“They could have put a bullet in our heads, put us in the ground and nobody was ever going to find us,” says Khan. “They believe there is an inevitable race war that is going to happen in America and possibly in parts of Europe as well, and they are preparing for that. They talk about white sharia law, and getting women back where they belong – to only having children to continue the white race. Weapons and alcohol are everywhere, and my weapon is my camera.”

A rising tide of hate

Journalism through documentary film has not had the Trump ‘fake media’ branding as yet, but it seems to be doing something akin to ‘LP journalism’.

“That’s why we are seeing them becoming as popular as they are,” explains Khan. “Broadcasters are not in a position to delve deeper into so many stories. The long form is just not there any more, but the appetite amongst audiences is absolutely there.

“We need more films more easily available so we can get people to understand certain topics and the complexity of them,” she adds.

Other memorable inputs came from Zach Caldwell with regard to Charlottesville and Javier Manzano.

Caldwell says: “Six months before the white supremacists rally and terror attack in Charlottesville I was in Florida at one of President Trump’s first victory rallies and I was verbally abused. My origins and my existence were questioned. Hateful eyes were cast upon me for having the double faults of being a member of the press and being a person of colour. Since then I have witnessed a rising tide of hate.”

Manzano focused on the value of the Rory Peck Trust, which admitted through new director Clothilde Redfern that it has only been able to answer 20 per cent of requests for funding help in the last year.

“It has been the angel on our shoulders for so many years, with training and support so we can do our job just a little bit more safely,” he says.

Regarding his trip into Western Mosul, he praised the local Iraqis: “They had the grace and courage to talk to us in the worst days of their lives.”

Talking about the vital local translators and producers, he says: “We leave and they stay, and they have to deal with the consequences of the fall out of our reporting at times.”

The Martin Adler Prize, awarded by the Rory Peck Trust trustees, was a posthumous recognition of the great investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, killed by a car bomb in October last year. Her journalist son Matthew collected the prize and was in the strange position of the mother of a murdered journalist presenting to the son of a murdered journalist.

He says: “Things have gotten worse. Why are journalists being murdered in Europe today? There is too much weight on our shoulders.”

One of the biggest audience roars on the night was for Tina Carr, who after a 21-year stint as director of the Rory Peck Trust had recently retired; Sarah Ward-Lilley, Trust chair, thanked Carr for her “incredible commitment to the freelancer cause, and her tireless fund raising”.