At last week’s Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition in London, the Creative Cameras teams from Edinburgh’s Heriot-Watt University and the University of Glasgow showed two new methods of achieving 3D imaging using just a single camera, or even just a single pixel.

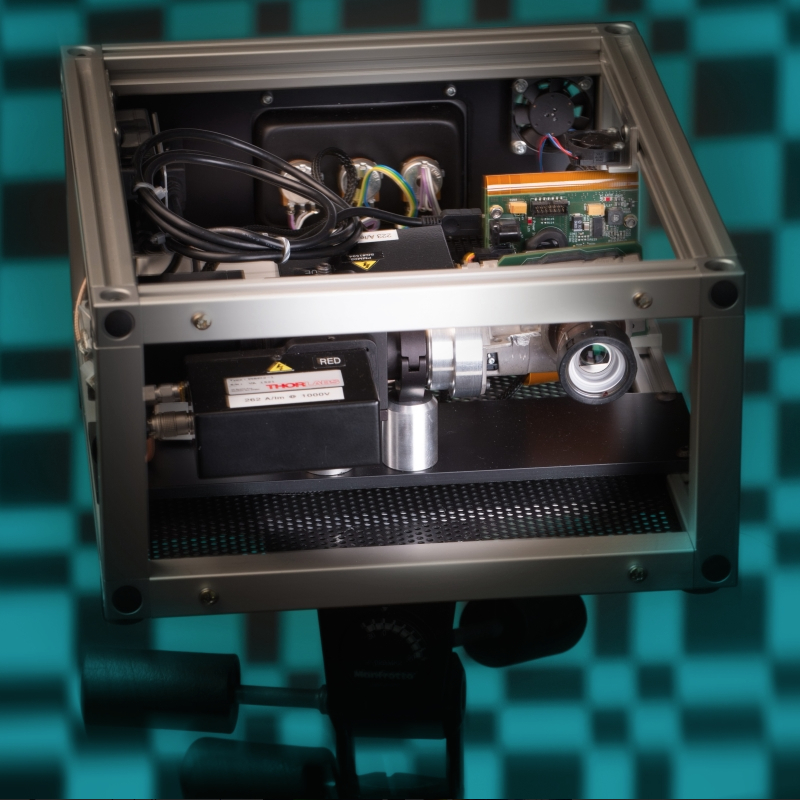

The camera developed by Glasgow researchers can take images way outside of the normal visible spectrum, using just a single pixel (or photodiode) instead of a normal camera with its lens and array of millions of pixels.

It uses a technique called “computational ghost imaging”, which uses “structured illumination” via a data projector, to shine multiple patterns (which look a bit like a random, ever-changing crossword puzzle) on a subject, which are then captured by a single detector. Where the white squares of the puzzles overlap with the object, the intensity of the light reaching the detector is higher, and the more patterns are projected (over no more than a few seconds at 650Hz – and as DMD projectors can do more than 20KHz, that time could be significantly reduced), the higher the resolution that results. The pixel can be made sensitive to nearly any colour, and a computer algorithm uses the reflected light and the mirror patterns to produce images.

When a set of single-pixel sensors is used together, the system can capture all the information that a conventional 3D camera could, recording all the contours and shading perfectly. Colour information can also be captured, by using three single pixel detectors. Interestingly, the shadows on the object are not determined by the position of the light source, but by the position of the detector. From the shading of the images, the surface gradients can be derived and the 3D object reconstructed.

If all it could do was to replicate a conventional 3D camera (even if it could be done more cheaply – and the single pixel sensor is very inexpensive), it mightn’t be so interesting. However, its ability to gather images in the ultraviolet range or across the infrared range (or even from a wider range of electromagnetic waves), gives it a wider range of uses. By using short wave infrared imaging, for example, it can see through some types of materials (such as paints in artworks), or dense smoke, and would be useful for medical diagnostics, night vision, or programmes on art history.

It would also possibly be a useful method of adding 3D information to a conventional 2D production, using light sources outside visible wavelengths to help capture action in 3D at a lower cost.

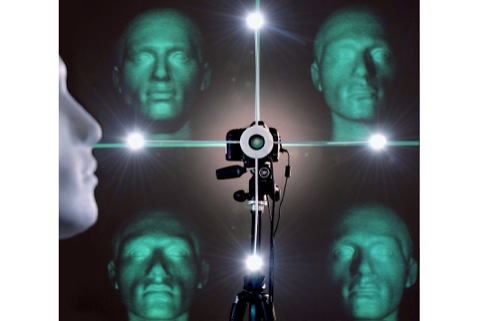

They also showed a cheap camera attachment for taking 3D pictures with a conventional single-lens camera. The Glasgow University team has built a 3D photo booth that takes 3D pictures using just one camera by using a technique called ‘photometric stereo’. The camera is surrounded by four lights that are used to illuminate the scene differently in each of four pictures. The differences in the shading of each picture can then be used to calculate the 3D surface and produce a 3D image.

www.eps.hw.ac.uk/institutes/photonics-quantum-sciences.htm

http://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/physics/research/groups/optics/

http://sse.royalsociety.org/2014/