George Jarrett attended the DPP Forum “File Delivery Made Simple” and discovered that striving for simplicity can be very complex.

Fishermen have their friend, and so do content producers. The Digital Production Partnership (DPP), not satiated by creating the AS-11 delivery standard, has developed an undeniable drive that is taking it into many associated areas where it can push for and set more standards, reduce others down to producer-speak bullet points, and offer people guidance in how to prosper in the file-based world.

DPP’s increasingly sophisticated bi-monthly forums attract large knowledge-hungry audiences from both the production and post sectors. At the most popular forum yet, staged at Channel 4, DPP chair Mark Harrison (pictured), currently seconded to the BBC encoding programme, said: “We are facing a very big moment in October – British broadcasting goes digital. And we only have a couple of dots to join in the form of programmes to finish and deliver.

“When we created AS-11 we didn’t recognise we could be the body to make the whole change process much simpler,” he added.

The DPP attracts a mixed ability group, so it runs sessions for the person who knows least. It put up eight people to tell the current story of file creation and delivery, and they all typified the wonderful support it has garnered from its national broadcaster membership.

The eyes have it

Andy Tennant (pictured below), technology director at ITV Studios, and DPP training collaborations head, covered technical standard and metadata issues from the standpoint of what producers must consider when they need to deliver an AS-11 file. Firstly, it will take longer to generate and deliver than a tape ever did.

“In our file-based world, metadata is absolutely mandatory. It must be delivered with the file, meaning that some of the paperwork that historically appeared after transmission needs to be brought forward,” Tennant said.

Typical of what the broadcaster would provide (and expect back) is the production number. Producer provided metadata should include a brief synopsis. Checking was Tennant’s third big subject. He asked: “How can I be confident as I learn this process that what I have got in terms of my file is something that has a reasonable chance of getting to a broadcaster, and on air?” The answers are on a helpful DPP checklist that starts with editorial sign off.

Tennant warned: “You cannot insert edit on file yet, so as you step through this process bear in mind that if you need to make a change, and you are in the process of completing your file, you are back into your edit and starting the process again. This makes final eyeball checks really important.”

The last chance saloon

Andy Quested, head of UHD technology at the BBC, locked onto the new emphasis on eyeballing. The eyeball review is a modern notion for the file exchange era, and it starts with setting up a screening room, and cutting out the bad habits of using computers or proxies to give final nods.

“It is a chance to sit down with a specific (DPP) check list. Don’t make the assumption that someone else is going to check it; that’s not going to happen anymore,” said Quested. “The review is the last chance for the producer, directors, DOP, production manager and editor to watch a programme, with the criteria of passing it technically.

“The contract says produce, make and deliver a transmittable programme, so it has always been there. This is about handing the responsibilities back to the producer, and actually allowing much more leeway for editorial interpretation,” he added.

It is not the editor’s responsibility to approve content for transmission, but if a file is rejected it bounces right back to the NLE. “The producer has to sign the certificate to say it has been checked and reviewed,” Quested said.

“The audience will decide if a programme is good or bad,” he added. “That is what has been happening in radio for 10 years. There is audience/producer and that’s how it should be. We are just going to reiterate what we all know anyway: this is not rocket science, it is about gut feeling.”

Fail every programme

The subject of automated QC and PSE fell to ITV technology strategist Rowan de Pomerai. Gone are the days of tape world QC with a person in a dark room armed with waveform monitors, audiometers and several monitors. Technical measurements are all wrapped in software processes.

“We can analyse files, preferably in faster than realtime, and give you the results to review, and to take into your human reviews too. It would give an inclination of particular areas you have to watch out for,” said Pomerai.

One problem is people wanting to create their own QC device and QC workflows – that will fail every programme. Pomerai said: “Buy any QC product. But turning on all the tasks and plugging it in will fail everything. The reason is that you can test so many things, and set so many parameters. Tuning this to test the right things is really difficult.”

This is where and why the DPP has looked at the fantastic QC definitions created by the EBU, and produced an intelligently shortened set of must dos.

“This goes through all the tests that the DPP thinks need to be done on a finished programme, and what the thresholds and tolerances are,” said Pomerai. “The idea is that vendors will be able to help us with setting up profiles for their QC devices.”

This will give producer a minimum baseline. In “real English language” the DPP explains mandatory tests for things that must be passed, and editorial and technical warnings. Photosensitive epilepsy is another area where the DPP has tested and approved various devices.

“Broadcasters will not be running a full QC on files certified as passing the DPP process. What we will do is basic file integrity checking, and there will be a spot check by the play out director to make sure it is the right bit of content,” said Pomerai.

Validate prior to wrapping

Shane Tucker, a development engineer at Channel 4 and DPP metadata app project manager, talked about the creation and export of a DPP AS-11 file, which is an AVC Intra 100Mbs file wrapped in with metadata and delivered as a single MXF file.

This MXF file has descriptive editorial, technical and structural metadata. Tucker looked at the vendor support of AS-11.

“Some are not currently providing full AS-11 files, but can provide the raw essence,” he said. “So you can do most of your work and you would import that valid essence file into the DPP metadata app and wrap in relevant metadata.

“There are many implementations of AS-11 out there, and when considering products one question you should ask yourself and the vendor is, how intuitive is the UI? Some products just present you with 60 fields and say there you go enter it.”

There is little validation and you might end up tapping in data already entered in your NLE. Do the fields drop down and offer options, or are they blank? Re-populating fields can lead to mistakes. The answer is validation.

“Look at validating prior to wrapping. As there are a lot of metadata fields it is quite easy to make the odd mistake, and have metadata not matching the essence,” said Tucker.

Do an anti-virus check

John Wollner, head of technology at BBC North and Nations, covered the issues around delivering files to broadcasters. It is about connectivity, the transfer mechanisms across that connectivity, security, file integrity and notification.

Wollner reviewed all the plusses and minuses of the internet, managed and direct service connections, and said that USB hard drives and LTO data tapes are verboten. His first like, after doubting FTP and the cloud, was third party accelerator tools.

“Security is the key issue. Bear in mind that broadcasters are receiving tens of thousands of files every year,” he said. “They do not have the time to manually check every file. We will use automated processes and if there is any non-compliance we will reject it.

“Do an anti virus check, because to broadcasters the worst nightmare is a virus in their system.”

Encryption is the key, but things to note include the fact that using other things like checksum might add delays to transfers. Neither the DPP app nor the DPP XML schemer will support checksum.

So what trips people up? “The AVCI class 100 codec for DPP is the SMPTE specification not the Panasonic spec. There is no debate or argument,” said Wollner. “The audio channels have to be BWF not AES, and that is another thing tripping people up recently. Audio channels have to be individual tracks (for HD).”

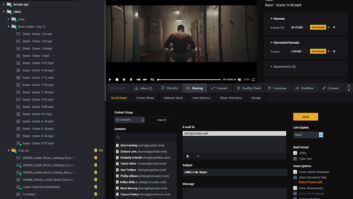

The third party accelerators provide notifications, a function that can be automated, and Wollner used (Signiant) Media Shuttle to demonstrate the ease with which files can be sent.

“Our children’s TV department get suppliers to deliver stuff using Media Shuffle,” he said. “As a test we got a supplier in Toronto to send a completed programme that was 38GBs. A 40-minute asset, it arrived in 38 minutes.”

A quality threshold

Kevin Burrows, CTO of broadcast and distribution at Channel 4, and DPP technical standards lead, looked at what happens to files once they are at the broadcaster. This is a nonlinear process full of side processes and lots of individual workflows going off to other platforms.

Focussing on the domain linear broadcast and keeping things simple, Burrows said: “The file would be available to broadcast depending on the timing. The metadata would have been entered or extracted within the conditioning and scheduling systems, so whoever is scheduling that programme will know where the parts are and how long it is. They put it into an automated schedule driving the play out server.”

There is an option. If the broadcaster cannot play out in the AVC file format at any time, there is the potential for a transcode, but this incident will be rare.

“It takes quite a long time to get something in place. We are seeing some quite big improvements in some of the Long GOP versions of AVC, and we have to start somewhere in terms of standardisation,” said Burrows. “At least then we have a quality threshold.”

Waiting for Insert editing

The strict procedures for recalling files were explained by Bill Brown, head of media standards at ITV. Editorial and technical corrections are more problematic in the file world, and you must replace original versions.

“Obviously if you send a file to a broadcaster or a play out provider you have not got a clue of how many times that file has been copied. So if you do not change the version when you alter the content either technically or editorially, you increase the risk of the wrong content going out with all the ramifications,” said Brown.

“The first stage if you must make a correction is to contact your broadcaster (media management department or programme planning) and get permission. Once you have consent, you go back to the beginning editing station. Once corrections are done, you have to re-enter the metadata, re-wrap the file, re-evaluate and QC it.”

Brown cited the questions around this subject: how close are you to TX, how good is your connectivity, how quickly can you transfer files, what are the limitations in terms of the workflow at the play out provider that is sending this file back to you, and how long will it take them to re-process the file content and get it onto servers.

“We have all known the days when we just dived into a linear tape suite and made a quick correction,” he said. “In the file world we still don’t have any means of insert editing, so we have to go way back to the first stage of the process.”

The letter of the law

Garry Metcalfe, a broadcast design engineer with Sky, covered the must-adhere-to subject of the EBU R 128 loudness specs. These are essentially a measuring method modelled on how the human ear responds to frequencies at different loudness levels. The result is measuring the average sound of an entire asset.

“There is no opportunity to be louder anymore. You are much better starting to open up your dynamics. Start to bring some nice fidelity into it,” said Metcalfe. “If you deliver R 128 compliant content it will go right through to the TX chain.”

Another EBU spec with lots of numbers required more plain English. “You measure the entire asset and there is the target loudness of -23, and that’s what you have to hit. If not correct, you simply move the whole mix up or down, give it attenuation and gain, until you get the correct value,” said Metcalfe. “There is confusion around tolerances on target loudness, but R 128 is the letter of the law. That said, most broadcasters have a built in tolerance anyway. Tolerance is built in for live content.”

The EBU PLOUD group is looking at adding a tolerance, and at loudness range.

“The other thing you have to ensure is that there are no peaks in the audio above -3db; the reason is if it is intended to go to a further compression codec such as Dolby Digital. The more you push it to zero, the greater chance of creating artefacts when you data reduce something,” said Metcalfe.

He ended by pointing at a major benefit. “If you are doing long form content it is arduous to measure it and find you have not hit the target loudness. It can be much more efficient to use a package and create your mix. The software will measure the content and calculate the offset that is required and automatically shift it to the correct loudness target.“

www.digitalproductionpartnership.co.uk