4K hype apart, the main theme of NAB2014 was virtualisation and the seemingly inexorable move to IP connectivity. What were the key thinkers saying, and what does it mean?

“SDN [software-defined networking] will happen faster than people think,” according to Charlie Vogt, president of what we are encouraged to call Imagine Communications but which we all know and love as Harris Broadcast. “Companies only have so much capex and so much resource,” he continued. “Have we convinced broadcasters and networks to move to SDN? Yes, we have. You will see some of the big networks making that transition very soon.” Vogt’s view, one which was repeated widely around the show, was that standard IT industry technology and techniques should be used wherever possible and, furthermore, that the possibilities are rapidly increasing. Software defined networking – the ability to abstract the data layer from the functional layer, so that the operator does not need to worry about how the content gets somewhere, just defines where it has to go – is a good example of the way things are moving.

For broadcast professionals, it means moving away from our traditional reliance on realtime, proprietary interconnections like SDI, and treating all content as data. In practice that means using IP, although Quantel’s Steve Owen did comment “if you were to start from scratch you probably would not pick IP, but it is quite good.”

Quantel – which now owns Snell so is back in the hardware business – was strongly pushing IP connectivity and IT routers, not least because of the vastly larger market and consequent economies of scale and scope for R&D.

A number of vendors pointed out that the market for broadcast routers is around $300 million a year; the market for IT routers is around $3 billion a quarter, or 40 times the size. They also pointed out that today’s 10 gigabit ethernet will be updated to 100 gigabit ethernet soon enough. IP routing is a great example of the way that other industries have paid for the R&D to benefit broadcasting. Richard Dellacanonica, CEO of Artel, told me “it’s the financial industry that drove all the latency out of IP”. Wall Street needed instant message transfers and total reliability, which means we benefit from the stability we need.

Artel was showing DigiLink, a signal routing system for SDI and ethernet which incorporates SDN to manage the end to end process. The devices are largely plug and play, and looking at it by eye there seemed to be around half a second of latency from camera to screen via JPEG2000 in SMPTE 2022 encapsulation over fibre. The vendors talking about IT routing – like Evertz, for example, as well as Artel and Quantel/Snell – all made the point that while the underlying technology may be different, we still need the broadcast control layer. It has to look like the router panel as we currently know it, even if there is SDN technology under the hood which is doing the routing. IP inside, with broadcast services like synchronisation and clean switching at the edge.

Virtualisation

Ericsson was one of many companies talking about virtualising processor-intensive operations like encoding. It has partnered with Elemental to put powerful encoding software onto a standard platform, which it calls Eve (Ericsson Virtualised Encoding). The purpose of Eve is to be able to package content as it is called for, rather than saving it in an ever-increasing number of formats. Within three years, 90% of the traffic on IP networks will be video, with 15 billion video-enabled mobile devices in use.

Elemental believes that consumers will pay for quality and resolution, so achieving the best compression performance will be a critical performance factor. Hence Eve, which can be scaled up and down on a virtualised platform as required. Harmonic, too, was showing encoding on virtual machines, with its VOS platform. The company still has a strong appliance business, but sees virtualisation as the way things are going. It also has a revenue-sharing partnership with cloud service encoding.com. The first implementation of the VOS platform, Electra XVM, also including playout automation, graphics and branding as well as high quality compression. To match the flexibility of the virtualisation it is available with different pricing models, allowing users to buy or rent scalable licences.

One of the applications Harmonic suggests is for local and regional playout, as a point of insertion for localised content. This application was the first big announcement from the new Grass Valley, formed from the merger with Miranda and based largely on Miranda technology. Essentially, this puts the localisation point at the remote headend, in the form of a simple switch and a solid state disk. Local content is delivered to the disk in advance (it stores 88 hours), and control is sent in the cloud to switch from master to regional services as required. There is no mission-critical reliance on the cloud, and you can even function over 3G or 4G if the internet cable gets dug up. Most important, because all you have at the remote headend is a simple switch and an SSD server, sitting on a single rack-mount card, you have no moving parts at all so no risk of failure, and a total power consumption of around 45W a channel so no need for air conditioning. It can be installed simply by connecting a couple of cables – a simple web server is included for remote set-up – so installation costs are virtually zero, too.

Playout

“Controlling automation is not a problem any more,” according to Ian Fletcher, whose business card now says Grass Valley CTO for playout. “Automation should be a business problem.” Pebble Beach is also addressing the business issues of playout. There is an increasing need for channels to be operated automatically, with remote monitoring and error reporting by exception. To meet these needs it has developed a web client which it claims to be as responsive as the traditional, directly connected fat client.

The web client will connect to any of the Pebble Beach automation systems over any network. Within it is a new product, Lighthouse, which provides a dashboard for the simple overview. It gives the user monitoring by exception, allowing fewer operators to control more channels by presenting them with only the information they need.

One company at NAB was claiming to manage “the world’s largest television catch-up service”, despite it being something that few of us will have heard of and fewer can use. The British Universities Film & Video Council now has more than a million programmes available online, for access by registered students. The network is powered by technology from Cambridge Imaging. Inevitably for a service with virtually no funding and no revenue stream, the operation is largely automated. Whole broadcast transport streams are captured, with the metadata stripped out from the EPG.

Another company doing unexpected and powerful things in content and rights management is Counterpoint Systems, which came out of the music industry to offer software systems to manage the financial status of contracts. Users include BBC Worldwide, which uses the software to track its programme sales deals and co-productions, and DirecTV in the USA, which uses Counterpoint to pay individual channels their share of subscriptions. One of the many acquisitions announced at or around the show was the acquisition of Pilat Media by Sintec. The two companies are pretty much in the same space, so it will be interesting to see how they progress.

The former Pilat part of the company is focusing on OTT, managing content alongside the back office routines. It collects feedback from users to drive new revenue opportunities. Meanwhile the former Sintec people unveiled version 4 of OnAir, now on a common platform for linear and non-linear delivery with better communication between all users.

Quality

VidCheck was promoting its second generation automatic QC software, which now runs four files simultaneously, each faster than realtime. The tests are defined by templates, some of which are supplied as standard: iPlayer and DPP are in the first batch. Users can quickly set up their own by running a perfect piece of content through the machine and using that to define a template.

Telestream also has DPP (AS-11) validation as part of the latest release of its transcoding platform Vantage. And the whole platform is now available on Amazon Web Services – you can even buy it from Amazon Marketplace. Telestream also talked to me about a new piece of software which is currently in beta but looks like being a life-saver. Switch is a universal player, making a fist of decoding any video format at all. It is rather like VLC, which many of us rely on, but with the added benefit of using legal codecs throughout.

The other great benefit of Telestream Switch is that the player-only version is free, and a Pro version (which allows for audio shuffling, AS-11 metadata and more) will be a hardly scary $295.

Perhaps more unexpected from Telestream is a tool to automate promo production. Given that a single programme could need 20 or 30 different promos for times and platforms, the Post Producer module takes in a template from one of the three As’ editing systems and churns out all the variants automatically. This is similar to Pixel Factory, the popular product/service from Pixel Power. James Gilbert was talking about the $1 promo, on the basis that his automated system could produce several hundred a day on a system that if you buy it would only cost around $50k. As Pixel OnDemand it is available on an opex basis, allowing you to buy processing time by the hour.

On the Dolby stand there was, to my eyes, a revelatory demonstration, of a new high contrast monitor. As far as I understand it, there is a pixel-for-pixel blue LED backlight which illuminates a high output phosphor layer (the newest lamps from Photon Beard work the same way) which then pass through the LCD panel. The result is high brightness, of course, but also a genuinely extended contrast range, real detail in the low lights and blacks which are actually very nearly black.

I am a great believer in high dynamic range and high frame rate being much better ways to improve perceived image quality rather than simply throwing more pixels at the screen, and this demonstration was excellent. On the other hand, the Dolby glasses-free 3D screen was not so good, causing this viewer at least to see some unpleasant rippling artefacts. Down on the SGO stand was a screen from a company called StreamTV, though, which gave a much more solid autostereoscopic 3D image with a very wide viewing angle. The technology could be built into consumer electronics by next CES.

Cloud

And finally, back to the concept of putting content in the cloud. Margaret Craig, CEO of Signiant, told me emphatically that “no sensible CFO is going to allow a business to build its own data centre today. If public cloud storage is so cheap, why would you do anything else.” Signiant’s Skydrop service goes quite a long way to eliminating the connectivity issues which could make that happen. On the other hand, Amberfin’s Bruce Devlin cautioned “data centres are not making any money at the moment. Margins are too tight. The content we are working on needs uncompromised quality, but you cannot do that for 13c an hour which is what Amazon charges.”

Forbidden Technologies pioneered editing in the cloud five years ago. Among its new functionality this year was the ability to connect a Sony camera, which generates its own proxy, directly to the cloud for instant edit access from anywhere. “You have to offer more for less by changing the workflow,” according to Forbidden’s Greg Hirst.

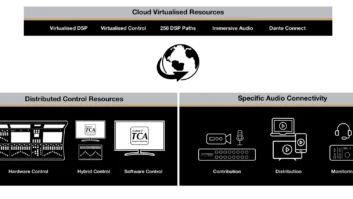

At Nevion, which specialises in delivering high quality content over IP circuits with very low latency, it is all about creating “a virtual environment with the best people skills, wherever they are,” according to CEO Geir Bryn-Jensen.

The last word, like the first, goes to Imagine’s Charlie Vogt. “Technology should just be the enabler for revenue generation – the content should be the differentiator,” he told me. “We have to make our customers as competitive as possible, as nimble as possible. Ten years from now, Netflix will look like ABC.”