It has been commonplace in the media industry, ever since the pandemic, to claim that employees prefer hybrid working to office working, and that the hybrid world is here to stay. But do we actually know this to be true?

It has been commonplace in the media industry, ever since the pandemic, to claim that employees prefer hybrid working to office working, and that the hybrid world is here to stay. But do we actually know this to be true?

The DPP, in partnership with Signiant and Wasabi, has conducted the first ever detailed research into hybrid working in the media industry. The project, which combined a detailed survey of 80 companies with workshops and interviews, looked at all aspects of hybrid working: from the enterprise toolsets required to enable collaboration across a distributed workforce; to new technologies and workflows in both live and recorded production; to workforce behaviours and attitudes.

The findings have now been published as Hybrid Working in the Media Industry: Are we equipped? And what emerges is a startling picture of a divided workforce.

The first myth to be exploded is the idea that we have settled into a new, and enduring, way of working. In reality, most of the respondents in the research believe we are simply living and working in another phase; one that will surely change. When asked if they thought their organisation would be working the same way in five years’ time, 72 per cent of respondents said no. When asked about how hybrid working has impacted various aspects of working life, the first signs of disharmony appeared.

The first myth to be exploded is the idea that we have settled into a new, and enduring, way of working. In reality, most of the respondents in the research believe we are simply living and working in another phase; one that will surely change. When asked if they thought their organisation would be working the same way in five years’ time, 72 per cent of respondents said no. When asked about how hybrid working has impacted various aspects of working life, the first signs of disharmony appeared.

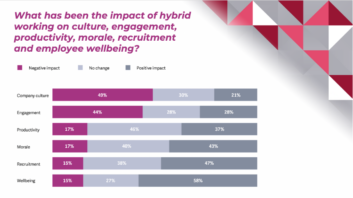

It became evident that, while hybrid working is seen as having a positive impact on the wellbeing, morale, and even productivity, of individual employees, it comes at a cost to the collective. Many feel that company culture and engagement has suffered.

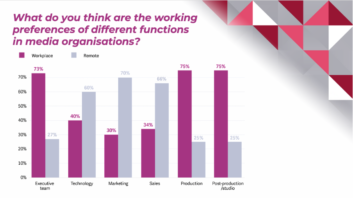

Any senior manager – or HR director for that matter – would tell you that if the personal and collective are in opposition within a company, tensions will eventually arise. And perhaps that partly explains the differences in response when different functions expressed their preferences. Those in senior management prefer more time in the workplace. And so do those that work in the creative part of the industry; in production and post production.

All the evidence of this research project indicated that those who work in production have returned almost completely to pre-pandemic ways of working. This doesn’t mean creatives have rejected the tools and technologies that enable remote working. Far from it. Those capabilities have simply fed the magpie nature of production: show a producer a new workflow, and you’ll just have just added to their options.

However they are working, and whatever tools they are using, people engaged in the collaborative endeavour of storytelling, and the hugely complex project that is the production process, need to be together.

Funnily enough that gives them something in common with senior management, who also tend to be focused on a collective endeavour in pursuit of a particular goal. And that may explain their similar preference for the workplace.

Does it really matter that some groups in the media industry want to work differently from others? In many ways it has to be a good thing that people get to work in a way that suits them. But the reality of running organisations in periods of constant change makes this benefit not entirely simple.

The industry is in turmoil; unable to match the manufacture and supply of content to the price the market is prepared to pay for it. But repeatedly, across different pieces of work, the DPP hears of challenges with driving change through all areas of media companies.

The number of media companies that are both producers and publishers has been steadily declining for years. So perhaps we are seeing a gradual separation of production and non-production cultures, with the publishers reshaping as more corporate entities. If so, I can’t help but feel something is being lost. One only has to look at how little the writers’ and actors’ strikes in the US, and the commissioning slowdown in the UK, have been discussed outside the production community. It has sometimes felt horribly like the indifference of those inside the walls to those outside.

Historically, the studio, broadcaster, or network that both made and distributed its own content, from its various physical locations, held the various working cultures of the media industry together. It was always an uneasy harmony. But ultimately everyone was united by a common purpose, and common passion for the creative output.

If we lose the common passion then do we lose the joy?