The coronavirus pandemic has led to people watching more TV than ever. Content consumption has substantially increased, and many TV channels have recorded some of their best ratings in years.

The TV industry relies upon ratings. These ratings tell the channels and their advertisers which shows are most popular, and which times of the day capture the largest audiences.

Streaming platforms such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Disney Plus, ITV Hub and BBC iPlayer have only recently been added to ratings listings, but each of the operators can measure viewing of content on their own streaming platform. Some, however, are reluctant to release this data.

Traditional TV viewing figures are produced by specialist ratings agencies, including BARB, Nielsen, and Kantar. For free to air satellite and terrestrial TV, the number of viewers for each channel at different times is measured using selected panels of viewers, and everything that the viewers watch is logged.

Unfortunately, these panels represent a very small sample of the viewing public.

For example, in the UK, BARB collects and distributes TV ratings. There are about 5200 BARB-monitored households from a total of around 27 million TV-equipped homes.

In the US, Nielsen is the most widely used ratings agency. There are about 27,000 Nielsen-monitored households from around 120 million TV-equipped homes.

This means that the ratings used by over the air TV channels, programme makers and advertisers are based upon a sample size of approximately 0.02 per cent.

The TV industry makes decisions about which programmes to commission, continue or drop based upon these ratings. How much advertisers pay for particular spots is also based on these ratings. With only one in every 5,000 homes being sampled, there is much criticism within the industry about the accuracy of this data, especially given the financial implications of such potentially misleading information.

Subscription platforms (such as Sky) can measure their own viewing figures with greater accuracy by interrogating their own branded set top boxes. In the UK, Sky collects data from about 500,000 set top boxes, which is approximately 4 per cent of their total subscribers. Unfortunately, this method is not available to non-subscription platforms.

In the US, Nielsen has started providing ratings for popular streaming platforms. Netflix has responded to these ratings based on viewing panels in a statement: “The data that Nielsen is reporting is not accurate, not even close, and does not reflect the viewing of these shows on Netflix”

As Netflix can measure every single time that their content is streamed to a subscriber (a sample size of 100 per cent), they can be confident in their own conclusions.

Some TV set manufacturers have built software into their devices that detects what their viewers are watching so that they can provide data to third parties. American TV set maker Vizio did exactly this, but ended up losing a $17 million class-action lawsuit for allegedly ‘spying on their customers’ viewing habits, violating privacy and consumer-protection laws’.

Within the EU, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) covers information that relates to an identified or identifiable individual. Essentially, if you can know who the person is, then you must obtain their explicit approval to collect, store and forward (or sell on) their data. Breaching GDPR regulations can be very expensive for a business, with a maximum fine of €20 million, or 4 per cent of annual global turnover for offenders.

Recently, a small UK company called TVA Group developed and patented a solution that collects large-scale live TV viewership data without infringing GDPR and consumer-protection laws.

Almost any Smart TV that is connected to the internet can utilise some of the interactive capabilities of today’s digital TV transmission standards to tell TVA whether it is tuned to specific channels.

By collecting this data and processing it to identify regionalities, TVA is producing real-time dashboards and historic reports that show, very accurately, what is being watched, where, and to a precision measured in seconds. This can be associated with specific programmes or commercials on individual channels.

In order to comply with GDPR, the TVA solution cannot identify what was showing on any given TV set, but can tell you how many sets in a given geographical area were tuned in to a specific channel at a precise time.

This can detect how many people saw a particular programme or commercial or, for example, whether the moving of live sports coverage between channels to avoid a clash with the news resulted in a loss of viewers. Traditional panel-based ratings collection can only report this type of data many hours or days later, and as we have seen, with dubious accuracy.

Online TV viewing is clearly gaining in popularity, and data from a channel’s streaming platforms can also be incorporated into TVA’s data analytics and reporting engines to provide an even broader view of total viewership.

Despite their small size, this UK company is successfully producing accurate live TV ratings for over 50 clients in an industry that has been poorly served by the established providers.

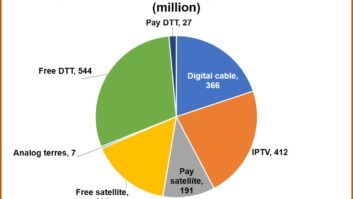

No single solution can measure the entire range of ways in which we now consume television content, but as the coronavirus crisis has shown, live free TV is still the predominant viewing platform, and likely to remain so for years to come. And if that is the case, shouldn’t the TV industry know what people are really watching?