A growing number of leading filmmakers have begun to explore how stereoscopy can enhance a story’s dramatic potential, by using the third-dimension as narrative element. In a sense the first phase of the new wave of digital stereo 3D has been passed.

The technical issues, while not completely smoothed out, are well understood and the technology has become commoditised. It’s time then to concentrate on not just technically accurate 3D to create a comfortable viewing experience, but for a creatively enhancing 3D that lifts content into the artform of filmmaking.

Certain filmmakers have instinctively reached for artistic metaphors with which to describe the new medium.

Working on Hugo, Martin Scorsese likened the technology to cubism and sculpture, understanding that characters and objects can be seen from new perspectives and need no longer be fixed to a flat canvas.

“With sculpture you walk around it so it becomes something different every place you look,” he says. “In doing so you are visually performing a tracking shot. Suddenly the sculpture has a very powerful presence with different aspects to it and that is the effect that 3D delivers.”

Wim Wenders has also compared 3D to sculpture. Struggling to find a way to capture the choreography of Pina Bausch on film, he claims, “3D could open out the flatness of the cinema screen and give dance the depth and sculptural quality it needed to work cinematically.”

Filmmakers have traditionally represented depth using a variety of techniques that have become ingrained in our understanding of what it means to watch a motion picture. Techniques such as depth of field, movement, framing, perspective and other cues like shadow and texture can convey the depth of a scene.

Yet, as Wim Wenders argues, “We have to deal with an art that has established itself over a century, with an incredibly intricate and elaborate grammar and vocabulary that we love and cherish, but we which we should perhaps see as some sort of a mistake — a two-dimensional film with the second eye missing.

“If we agree that 3D is indeed not only a new technology, but also a new film language, it is obvious that it needs its own grammar and its own vocabulary.”

New visual grammar

Getting there means shifting the focus of what it means to think about 3D from a technical discipline or a cost equation toward the creative potential of stereo to enhance mood or emote character or help convey a connection with an actor’s performance, a landscape or a narrative.

Already terms like ‘convergence’, ‘interocular’ and ‘screen plane’ are forming part of the burgeoning new visual grammar that might soon become as natural to filmmakers as the ‘close-up’.

A new stereo language could get incredibly technical, wrapped up in calculus for measuring interaxial distances against focal length or analysing disparity values for every pixel. Yet many of the artists we interviewed say that they prefer to use more descriptive and instinctual terms such as dial up (or dial down) the stereo, ‘punchy’ or ‘shallow’, ‘volume’, ‘immersive’ and ‘roundness’ or simply ‘give me more/ or less’ 3D.

“Filmmakers are adopting a new language to describe how they want the 3D to work for a particular scene,” observes Jamie Beard, a pre-visualisation supervisor who worked with Steven Spielberg on The Adventures of Tintin. “It is not an exact science and there is no creative industry bible you can refer to. Consequently, descriptions can be a little broad, often using a very emotional type of language, but nonetheless one that is understood in context.”

All of this presumes that rather than isolated or added-on, stereo 3D is embedded into the design of the film and all other craft tools from the get-go.

“It’s hard to simply separate out 3D and state with certainty what it brings to a drama,” says Rob Legato, the Oscar winning visual effects supervisor for Hugo. “You may as well ask what function colour alone has on the impact of the drama or how you divorce selective focus depth of field, lighting and production design from the story telling. The point is that when used as an integral part of the filmmaking process 3D helps create a unique emotional response that, were you to see the same film in 2D, then the emotional content would be diminished.”

Those filmmakers we interviewed believe passionately that 3D is a creative discipline and that only a creative approach will determine whether stereo 3D will this time stay for good.

We selected to case study the very best 3D work in each genre since the inception of the new age of digital 3D filmmaking in 2008 and have talked to the key filmmakers involved.

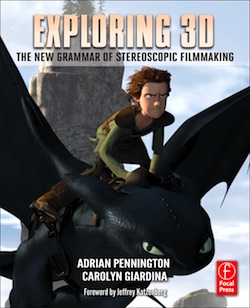

These include directors Martin Scorsese (Hugo), Wim Wenders (PINA), Henry Selick (Coraline), Dean DeBlois and Chris Sanders (How to Train Your Dragon) and Baz Luhrmann (The Great Gatsby) as well as the teams behind Avatar, Flying Monsters 3D and U23D and live sports productions like the FIFA World Cup 2010.

As Martin Scorsese argues: “3D is an element to be used like sound and colour but when new things are introduced there is always a resistance to change. We are headed toward a day when 3D will be accepted as matter of fact just as colour design, sound or the absence of sound, but it will take dialogue between filmmakers to push and change the perception of 3D and to give it a new language. The technology will inevitably find a way to become less expensive. At a certain point 3D will be as inexpensive to use as colour or the digital intermediate process and when it finds that level it will become normal.”

Exploring 3D: The New Grammar of Stereoscopic Filmmaking, by Adrian Pennington and Carolyn Giardina, is published by Focal Press

Picture credit: “How To Train Your Dragon” © 2010, Courtesy of DreamWorks Animation

By Adrian Pennington and Carolyn Giardina